A Story About Him or: Do You Understand Contemporary Arts?

“Ladies and Gentlemen – we

got him!”

Paul Bremer, the Bush administration’s

point man in Baghdad, 13/12/2003

This Hollywood-like line said by Mr. Paul Bremer at the press conference

in Baghdad was an announcement that U.S.

soldiers have caught Saddam Hussein. They were probably meant to stay

remembered by historians in the same way as first words of Neil Armstrong

stepping on the Moon, “That’s one small step for a man but one giant

leap for mankind”. Mr. Bremer was standing in front of a dozen, mainly Iraqi

journalists, who started to shout in ecstasy when he announced this. Not to

mention that there were no ‘ladies’ in the room, but Mr. Bremer probably had to

be politically correct and include all of ‘us’ in this celebration. The images

that were shown after are still to be discussed by the public opinion worldwide

as, possibly, a major violation of human rights: ex-dictator was reduced to an

image of a wild beast, with long, messy hair, and long, white beard; a doctor’s

hand in gloves was touching him with precaution, examining, showing us his

teeth, just to be sure he is not contagious anymore. We could argue and say –

what else would you expect to see of a person, or in this case - a dictator,

forced to hide nine months in the ‘spider hole’? But U.S.

officials were quite surprised to find out that this wild animal won’t bite

them, saying that he was “talkative and cooperative.”[1] Why

wouldn’t he be? The effect of this capturing was not as expected, since we were

supposed to believe in the big celebrations of happy Iraqi people while

watching a direct broadcasting of a group of 25 men jumping happily at some

highway just for the eye of CNN cameraman.

Nevertheless, this attempt of Bush’s administration to show to their voters and the rest of the world that their mission in this country is full of success, while hiding the main reason for their presence there, is just one small step in the walking-tour of spreading global capitalism today, and just a small reminder of our reality. This paper will be a story about another Him, a sculpture of Adolph Hitler made by artist Maurizio Cattelan in 2001 and exhibited as a part of the exhibition curated by Ydessa Hendeles in Haus der Kunst in Munich, during winter 2003/04. More precisely, this paper will be an attempt to test some new approaches in understanding contemporary arts, but also a small diary on what happens when you let your object to speak back (Bal, 2002: 45).[2] This will lead us right to the field of cultural analysis, forcing us to re-think the position and function that contemporary intellectuals and artists can have today, as well as their possible fields of re-action. Adolph Hitler was never caught by Allies forces in World War Two, and the question will always remain the same: would it be different if we got him?

Partners or:

Why are we more shocked by devastated teddy bears than human bodies?

Where did I see ‘Him’? Maybe at the most logical

place – in Haus

der Kunst, in Munich, in the

building created by him and his Nazi-partners in 1937

to promote ‘real’ German art. So, more than sixty years later, German-born

Canadian Jewish art collector and curator, Ydessa Hendeles, was invited to make

her own exhibition, probably marking a new chapter in the history of this building.

In this moment, we won’t be so interested in this remarkable exhibition itself,

but only in the part with Him. It is also important to mention that this

exhibition was obviously clearly and precisely thought of, placing the visitor

in the system with clearly defined path, making narrative of the exhibition

itself.[3]

Visitors know this from the start, after reading a clear introductionary text

saying that some doors are closed and locked just for the purpose of this

exhibition, and everyone is supposed to follow more or less the same path.

After entering, you are able to see three works of small dimensions in the

first room (Self-portrait by Diane Arbus, The Wild Bunch, Minnie

Mouse carrying Felix in cage).[4] After this room, you can choose to go right or left, but it is most

probably that you will continue to the right, attracted by specific cabinet of rarities – to the part named ‘Partners (Teddy Bear Project)’, work made by Ydessa

Hendeles herself after she posted an invitation to buy photographs of teddy

bears worldwide. This is probably unique opportunity to see more than 3000

photographs of teddy bears in different situations, or, more precisely, people

with their teddy bears in different situations, marking XX century as a century

when this habit was invented.

After examining two rooms full from top to bottom with teddy bears’ pictures, you will enter into the next one, empty and a little bit cold, seeing a boy or a small person kneeling, but showing you his back. You will have to walk, come closer and be surprised for yourself – it’s Him, it’s the sculpture of Adolph Hitler on his knees. The most disturbing thing about Him you will realize immediately is particular impossibility to ‘catch’ his glance, you can’t see into his eyes. His face looks a bit intense, his mouth is tightly closed; this is the face you will find in almost every photograph of Him. His eyes are looking somewhere above you, making it impossible for you to communicate. It is exactly in this part where this artwork really starts to work: this emptiness will make it clear that Him isn’t a ready-made answer, but a question. You are forced to confront with Him and his emptiness, confronting your own system of belief, confronting your own impossibility to interpret Him – you will have to think first. Teddy bears are usually an essential part when the child is about to fall asleep, serving as a buffer for the dark world of dreams, for the dark world of unconsciousness. Maybe we could see Teddy Bear Project serving the same purpose here: making it easier for you to enter into the next room, where you are forced to confront with your own identity system – and meet Him.

Supposedly the most usual way to interpret artwork from the art historian discourse would be to start with the question about the author and his oeuvre in general. So, who made Him? It is one of the most popular artists of today, Maurizio Cattelan, born in 1960 in Padua, Italy. The words that are usually used to describe him are “a joker” (Wakefield, 2000:1), “the court jester of the art world and the cartoonist of conceptualism” (Lewis, 2003:1). Indeed, after taking a closer look into his work, you will probably have the same impression too. Cattelan is using humor in a very specific way, most of the time being ironical, even self-ironical, or just trying to provoke sleepy environment in which he is supposed to make an exhibition. But, this humor has a specific function: it works as an injection of anesthesia making it easier for everyone to hear the painful truth.[5] The list of his well known works is getting bigger every day: the horse suspended from the ceiling; peace made of rubbles from a terrorist bombing in Italy; his Paris dealer Emmanuel Perrotin forced to wear a giant pink phallus-like rabbit costume for six weeks; a miniature diorama of a little squirrel, lying on the yellow kitchen table after committing a suicide, with his tiny handgun beside him; a copy of Vietnam memorial black granite with the inscription of years when English National Soccer team has lost games, exhibited in London; actor wearing a giant Picasso head in front of MOMA in New York, behaving like Mickey Mouse, referring to this institution as a high-culture Disneyland; stealing art work from the gallery in Amsterdam and displaying it as his own when he didn’t make it on time; sponsoring his own football team near Bologna made of immigrants from Senegal, wearing uniforms with the title “Raus”, etc. The list of his works is really long and impressive one, and interpretation of each of them deserves more space and time than we have here. Basically, his life story is his problem with authorities and subordinating to dominant systems. When he discovered the world of arts at the age of twenty, he knew he has found a right place to express all he had in mind. In comparison with the conceptual artists of previous generations, who still believed in radical changes of society and the world trough art, Cattelan is a symptomatic example for the only possible position contemporary artist can have today. He is fully aware that he cannot subvert a system of which he is part:

It’s more about portable utopias. It’s like admitting you can’t actually create a utopia: You can’t really imagine a brave new world. We are bound to work on smaller systems. [...] The margins of freedom are smaller and smaller, and we simply have to adapt (Cattelan in Obrist, 2002:1).

Instead, Cattelan has decided to make objects, “rhetorical sculptures” (Nickas, 1999): rhetorical sculptures in the sense that they are there to make questions, not giving only one answer. His works look like being based on some kind of detector whose aim is to find all well hidden cracks around us: his job as an artist is just to make these cracks visible. Rhetorical also as a way to make people speak about these cracks.[6] It seems like Cattelan is fully aware that every art object he makes will be closely examined by public, theoreticians, even politicians, and he is ready for that. With just saying a right (or, better, wrong) word in the right place, he forces people around to start to speak. In the case with Him things are a bit more complex: it seems to be more a story about people staying silent.

Cattelans’ diagnosis of this silence in German society was been made much earlier - in 1992 – but the curator was not ready for such an adventure. Invited to participate at the exhibition at Sonsbeck he was planning to advertise an imaginary Nazi rally, by putting posters and disseminating flyers and handouts all over the city. The curator was really angry, “Started screaming on the phone, saying: Do you know what you are talking about with the Nazi?... She said these issues were too delicate.” (Obrist, 2002). All he had to do was to wait ten years, become very famous and successful and to one day make Him.

The possible effect his rhetorical sculptures have could be seen in the example of La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour), today well-known wax statue of Pope John Paul II (recently sold for 900 000 euros), laying down after being hit by the meteorite. When this was exhibited in Poland, two Catholic representatives attacked the statue and tried to liberate the Pope, bringing this case to the parliament: the director of the museum was asked to resign, accused for insulting catholic majority from her Jewish background. But, no one has tried to destroy Him, not even to touch:

This time I wanted to destroy it myself. I changed my mind a thousand times, every day. Hitler is pure fear; it’s an image of terrible pain. It even hurts to pronounce his name. And yet that name has conquered my memory, it lives in my head, even if it remains taboo. Hitler is everywhere, haunting the specter of history, and yet he is unmentionable, irreproducible, wrapped in a blanket of silence. I’m not trying to offend anyone. I don’t want to raise a new conflict or create some publicity. I would just like that image to become a territory for negotiation or a test for our psychosis. [...] My mother used to say that’s impossible to clean a tile if one does not see where the dirtiness is.

Indeed, we have to admit and say that in the end, it wasn’t Cattelan who had invented a monster. The list of partners in Nazi history is very long, putting the responsibility on the whole society that participated in this horrible project of Him.

Next step in interpreting an artwork could be to look at the work itself, analyzing its structure. On the tag at the wall describing the name of the author, title of the work and material used for it, every visitor can also read that beside wax, polyester, and clothes used to make Him, Cattelan has also used human hair. Here we can find a clear reference to Auschwitz and other ‘working camps’ where human hair of imprisoned people was used to make clothes, just to show how economical human animals could be. The position that Cattelan has chosen – to show Hitler so tiny and on his knees – is putting you in a special relation to it: you could start thinking how is it possible that this boy, which Adolph Hitler certainly was once ago, could have done so many evil things.[7] This incredible discrepancy between his human smallness and his deeds will also stroke your mind. The fact that he has never regretted that is making this small boy with the face of an old man even more tragic. He is forced to be on his knees, pretending to pray when you look from the back, but this face is ruining everything: it is so clear that he is not sad, and he is not praying at all. He is just kneeling there like an empty signifier for you to interpret Him as you wish.

After these two short attempts to interpret an art work like art historians would probably do, the question remains what could we find out this way? Not much. The artist himself is giving us full freedom to discuss and interpret – even misinterpret – his work, just to make us speak about Him. By analyzing Him we did not get too far either: he is still standing there speechless. In the next part we will take a look at what could we do with the new tool in interpreting contemporary arts: we will talk about relational aesthetics.

Defending Contemporary Art:

Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics

While trying to make a documentary on relational aesthetics for BBC Four

a few months ago, director Ben Lewis had encountered a big problem: the

majority of the artists mentioned in the book with this title refused even to

talk with him. So, what is relational aesthetics? Nicolas Bourriaud used this

term in today almost controversial essay written and published in 1998.[8]

Working as an art critic, in this moment one of the co-directors of Palais du Tokyo in Paris, he felt the need to reply on all-around opinion about the

unintelligibility of contemporary artistic practice that has been established

already as a cliché. His aim was to try to create

a tool for better understanding of this practice, risking to be accused for

creating a new –ism: relationalism. The first

question he was trying to answer was what the most prominent artists of the

nineties have in common: taking the examples of Rirkrit Tiravanija who makes

dinner in the house of his collector leaving the necessary ingredients for tai

soup, Phillipe Parreno who invites people to join him on the 1st of

May at the factory line where they could practice their hobby, Vanessa Beecroft

exhibiting twenty identically dressed women with red wigs enabling the visitors

to see them only trough a small window, Maurizio Cattelan feeding rats with the

Italian cheese Bel Paese and then selling them, Jes

Brinch and Henrik Plenge Jakobsen putting a strange bus at the public square in

Copenhagen provoking riots in the city, Christine Hill working as a cashier at

the supermarket and organizing fitness exercises in the gallery, etc. Seeing

this way, all these artistic activities could look quite heterogeneous, having

nothing in common due to traditional aesthetic criteria. Believing that the art

of the nineties did bring something new, Bourriaud sees the reason for its

misunderstanding in the lack of proper theoretical discourse. In other words,

without a discourse, we are not able to frame it in the right way. In his

glossary in the end of the book, Bourriaud gives these definitions of relational art and relational

aesthetics:

Relational art: A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.

Relational aesthetics: Aesthetic theory consisting in judging artworks on the basis of the inter-human relations which they represent, produce or prompt.[9]

This theoretical standing point is throwing away romantic image of a solitude artist, deeply occupied with his own soul, his own pain, visualizing this in the form of an artwork. Artists of the nineties, according to Bourriaud, are completely turned toward existing relations, referring to the crises of today’s global society. Their works have this highly anti-capitalistic dimension, and the same could be said for the theoretical approach trying to explain them. In the artistic practice, Bourriaud finds the only space for the social experiments of today: “We must learn how to live better in the existing world, [...] instead of making the new one.”[10] Bourriaud finds exhibitions of art works as a place for new intervention, breaking always-the-same rhythm of life dictated by dominant system. Commenting that art has always been relational in certain amounts, as a part of social activities and base for dialogue, the thing that distinguishes contemporary artists is their inspiration with the society around them, creating works that will communicate with it. In other words, if you want to understand the society you are living now, try to understand contemporary art. Work of art is becoming a social interspace where “new opportunities of life are becoming possible”:

It is more important to create potential relations with your actual neighbours than say praising words to tomorrow. It seems as something small, but, in fact, it is something gigantic.[11]

Relational aesthetics doesn’t have the aim to be a new history of art, but a theory of form:

Artistic aura is no longer in the world hidden behind the artwork, nor in its form; it is in front of the work, in temporary collective form created while it is exhibited.[12]

Subjectivity is for Bourriaud something completely artificial, constructed and created, so he finds in the objects of art this otherness, subjectivity of the Other that is necessary for creation of the dominant “I”. Admitting that it’s impossible to create Golden Age in the Earth, nor to represent utopias, art should be “a place for meeting”:

Modernity existed in the imaginary world of oppositions. [...] Our development should not be based on the conflicts and oppositions, but on the discovering new connections and possible relations between different units, on new unions made by different partners.[13]

Partners – this word is bringing us back to Ydessa Hendeles’ exhibition and in many ways, this exhibition could be seen as a ‘relational’ one.[14] Nevertheless, in this moment, we will take a look what happens with Him if we use relational aesthetics.

What Can We Hear From Him?

The answer to this question is clear: nothing and that is exactly the

point. Him is standing at the position of eternal evil, and all we can do is be

numb in front of it too. Cattelan’s intelligent decision not to make Him in the shape and pose we all know Adolph Hitler – as a decision

making standing up man, but as a tiny boy on his knees - is exactly a point

that openness up the space for re-thinking and re-negotiations. Exhibited in

this particular building, at the House of Him, in the state where it is

forbidden by law to publicly exhibit pictures or representations of Hitler,

makes from this event a more than significant one. If we use the strategy of

relational aesthetics – not to analyze the past we have no idea how it really

looked like – but to talk about us, about today’s German even European society,

we could see where we could be taken by Him. This way, we

will not be seduced to fill Him up with all possible metaphorical meanings

he could be standing for. Instead, we should try to turn our gaze to the

surrounding society and try to find new ground for negotiations with the neighbors, the only partners for tomorrow we have. Seen this way, Him functions as a gigantic nail which hit by the hammer makes numerous

cracks all over the wall we believed was homogeneous and solid.

As a person who is taught to believe in the myth about the German Nazi past that happened centuries ago and not only few generations before, I was even more surprised to discover all these cracks. At the same time, two interesting encounters happened in my life, helping me to understand what is really happening here. First encounter took place during my visit to Munich and the exhibition when I was a guest in the home of an 85 year old German lady who used to be an artist herself. After the recent death of her husband, she started a small project of opening old boxes they have in the house, probably finding sentimental values in the things collected there. One day, she opened a box and there it was – parts of the Nazi uniform, accompanied with a black & white photograph of Adolph Hitler. She showed me this photo as a rarity while I was visiting, and the only thing we could do was to discuss the way the picture was made: Hitler was standing proudly in his always-shiny leather boots, and the other people around him were little bit blurred, showing to the viewer how ‘distinguished’ he was. I was not able to ask anything more, about the background of the story, how did they get the picture or something similar. I was afraid to hear the answer.

Second encounter happened few days later, when I asked my young German friend for a little help about some mysteries of the Nazi history. He looked at me, sighed and said: “I don’t know where to start”. Trying to make this situation more casual, I made a joke saying: “Well, start from your own family!” And he did. It was so easy, and I was really shocked to see how far this crack went. After a few minutes, a French friend joined our conversation, and started to speak about his grandfather. The crack was growing bigger and bigger now, and I had the impression that there is nothing that can stop this inevitable process. The story I had heard from them was quite terrifying: No, I did not hear confessions of their fathers and grandfathers of the things they did or saw, since they never heard something similar from them either. In their families this part of the history and their lives was censured for good, and the only breaking of this law happened in a few situations when my friends were witnessing when their family members, not being able to it stand anymore, exploded with the hidden animosity towards new Others in their societies: Muslims and Blacks. People usually store pictures with teddy bears somewhere deep in their family albums, considering them to be witnesses of the moments when they were soft or childish; but it seems that if Ydessa Hendeles had posted the advert to buy pictures of Him from family albums, the number could probably be bigger than 3000.

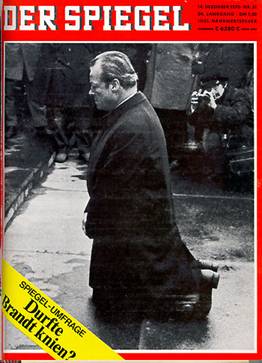

This problem that German people have with their censored Nazi past was hidden in one more thing: there was not a single mention in German newspapers about one event Cattelan’s work is clearly referring to. In 1970 somebody else fell on his knees in Warsaw, asking for forgiveness: it was German chancellor Willy Brandt.[15] While researching facts about this historical event, I have found a strange public opinion poll done by the newspapers with the question how did they find this act. From the 100 people asked, the majority believed that this was exaggerated, and we should be shocked with the fact that someone even thought about asking this kind of question in the first place.[16] This is bringing us back again to Him: it seems like Cattelan had a clear idea of making Hitler on his knees, in the exact same pose we find Brandt, but Him looks as someone forced to kneel in the name of political correctness, with the face that is still the same, hiding anger and hatred. Hitler did commit suicide, but his partners were forced to hide their feelings for good. In this point we are encountering with the concepts of guilt and responsibility: in this case, guilt is something that should be individual, personalized, and the executors must be punished for their deeds; but the responsibility is something that everyone who even agreed in their mind with the politics of evil has to take and be confronted with. This lack of confrontation and censorship of the recent past can only result as an impossibility to create ‘normal’ identity, and repressed facts will come out one day making more trouble than anyone could imagine.[17]

The repression of memory in the case of post-war Germany is something that has become the legacy of new generations.[18] As we know, in every attempt to create a strong national identity there is always one problem: you cannot do it without the help of the Other. As seen in the case with Him, this crack goes much further from the borders of Germany: today we are witnessing various problems all over the continent in the attempt to create unique European identity.[19]

Europe vs. her Other(s): Unity in Diversity?

Stories about constant terrorist attacks, images of destroyed synagogues, President of the European Commission Romano Prodi asked to explain the rise of new anti-Semitism in Europe... Symptoms we can see everyday on the news. What is the story behind it? If we take a look what the media considers as the main problems Europe is encountering today we will find two things: 1) problem of negotiating the new EU constitution and 2) new anti-Semitism. In the first moment, these two things have nothing in common. But, if we take a closer look, there is one thing they do have in common: EU hidden policy on the exclusion of the Others. In the case of constitution (or, more precisely, “constitutional treaty between governments” - Kerr, 2003) the problem is defined as a problem of two-speed Europe, or the existence of “slow wagons” as named by President of the European Commission Prodi (Prodi, 2004). In this definition lies the fact of existence 3 levels of division between EU countries: so-called first countries (countries that created EU in the first place) are considered to be “fast” wagons, and basically it means the club of the financially richest countries; Spain, as one of the opponents for the discriminating parts in the constitution that will exclude them to be in equal position in decision making, is member of the economically poorer countries within EU. New members of EU, basically countries of ex-Eastern Europe, are in the third level of division, making Poland as a main opponent to this new practice of exclusion in decision making as sketched in the constitutional treaty. The image that Europe still tries to project about itself among non-EU members as an image of artificial unity and strength is creating this problem, while the truth we find is completely different. Trying to accuse new members and the rest of the slow wagons for the problems EU encounters, ‘fast’ developing countries are just hiding the truth about themselves. Logic of global capitalism is controlling every part, and this constant need to expand the market has nothing to do with the official narrative of EU good will to help the less developed. The speed of any train has nothing to do with the slow wagons; locomotive is the one that dictates the rhythm.

Beside this separation of identities within the EU itself, another process in creating ‘European identity’ is also taking place, where we can find the answer for the second European problem, new anti-Semitism. In fact, European identity is created in the oppositions white vs. non-white, and Christians vs. Muslims, making the Black Muslim population as the extreme example for Otherness. Stories created by the media and politicians are following the narrative about various people invading Fortress Europe, coming from the East or the South. The ‘crisis’ in Europe is explained as a consequence of this invasion. The true Europe is trying to neglect a big problem of depopulation and lack of labor force needed to sustain the existing market as well as the existing social security and pension system. Europe cannot exist without import of new labor, nor help from their immigrants. The cataclysmic scenario for Europe would be if all these immigrants would really listen to the message from the radical right-wing parties and went “Rauss”. What would be left of Europe could be a thing to guess about.

The lack of understanding present reality can also be seen in the recent decision to bring new law in France that forbids the display of religious symbols in public institutions. Behind this diplomatic expression we can find a hidden attempt to forbid Muslim women to wear their veil, their burkas. This problem is not only problem of French politics, it goes much further – everywhere where Muslim women live in Europe. This fact of failure to live with this obvious otherness by dominant Western system is quite frightening. Paradoxically, this debate seems to be neglected by major feministic circles, and if they try to see it from the different angle, maybe we can find here new space for feminist fight. The reason for this probably lies in the predominant image of Muslim women completely subordinated to the dominant patriarchal system. Is this really the truth, or, let put this other way, does European society really differs from this? In his analysis of this habit of Muslim women in Germany, Mark Terkessidis has concluded:

The veil is something that

prevents the Other to be consumed. It is subverting the image that exotic Other

has in the process of constructing dominant “I” and blocks the way to – in the

case with the additional sexual connotation – the pleasure.[20]

His research among young Muslim women has shown that the decision to wear the veil is something that goes beyond the frontiers of just religious expression: this decision is in most cases individual and conscious:

Also, in most of the cases, they are using this strategy in the “silent revolution against their parents.”[22] The position to see but not to be seen by the dominant system is considered to be the main threat to our dominant strip tease market of women bodies, carrying the decision of these women to be integrated as a visible Other. Underlining gendered separation that exists in Western society, these women are throwing it into the face of dominant patriarchal system which has created, modified and hidden strategies of subordinating women’ otherness. The advertisement that invites young Dutch girls to join the army does not mean that the change in this game played by patriarchal system has really happened. In fact, believing in the narrative that women are equal in this society, girls in the army are just the sign that system has succeeded to reproduce its gendered – masculine – identity going one step further of not being defined anymore by sex/biological attributes. Girls will be masculinized and the army, as the most extreme example of patriarchal strategy for survival, will only be the next chapter in the story about Crusade warriors. This problem of Europe to really accept otherness is so clear in EU slogan: “Unity in diversity”. Real change should be “Diversity in Unity” and it seems we will need a long time to see this happening.

New anti-Semitism is something defined differently by politicians than theoreticians. In the case of journalists and politicians, new anti-Semitism is seen as exclusively practice of young Muslims, mainly in France, and connected to the Middle East crisis. Closer look brings out the truth that all these young people are alienated and marginalized by dominant society where they live, and in this radical expression toward Jews community they are actually informing us about these problems. It seems that politicians want to transfer this problem of discriminated Muslim population as a consequence of their immanent difference and vandalism that is now clearly seen in their behavior and hatred toward one of the smallest non-Christian population in Europe as Jewish has become after World War II. Trying to define new anti-Semitism, Slavoj Žižek is making a parallel with the old type that has been an effect of the process of defining strong national identities, while this new type is becoming universal expression of non-tolerance toward Otherness:

In this global sphere, every ethnic difference is eo ipso seen as ‘internal’ one, making that every nationalism is in fact a sort of racism, and every racism has a structure of anti-Semitism.[23]

The danger with the new type of racism is this structure that is ‘reflected’, racism square, who is easily able to take the shape of its opposition, struggle against racism:

If we have this in mind, the fact

that dominant Western European discourse is now trying to find a justification

for its fight against Muslim population showing it as an attempt to protect

weak Jewish community, could sound even more terrifying. New modes of exclusion

are taking their place and if politics fail to see them in a right way, the

reaction could be worse than we see it today, making this world a battlefield

for the armies fighting against each other one more time, where dominant

patriarchal system finds its force to reproduce itself in continuum.

Conclusion

After this short excursion, it seems that new generation of young people all over Europe will have a lot of work to do and problems to solve, problems so generously left by their parents. The best example for the role young people could have is found in the ‘bloody Balkans’: Milosevic was not caught by any army, he did not resign because people did change their mind setting with the generous help from the West; it was a big movement of young people who had a mission on the election day to take their grandparents by their hands and order them whom to give their vote to this time. Sounds too radical and not so ‘democratic’, but that was the only way to influence their future. The same role will probably be inevitable for young Germans, French, ... Europeans: an attempt to teach your family members how to live with all these Others around. The tragedy of the Holocaust is not only in the fact that the survived victims are dying – their executors are leaving this world without confronting with the past, leaving to the next generations the burden that is not theirs. As we could see in the case with Him, contemporary artists still can make some changes; they still can provoke the system. Relational aesthetics is one of the ways that can transfer the focus from the past to the present days: if we see Him in that way, we will not be caught up in the trap to discuss about victims and executors from the past (which, of course, should not be forgotten), but about concepts of exclusion of the Others in the contemporary Europe who must not become victims in the hands of some future executors. Serving as a field for discussion and new, sometimes even provocative readings of concepts in contemporary reality, cultural analysis should be a new force to show on the possible ways for the development of today’s global society, evading to be a pure intellectual exercise. The example of that caught dictator from the beginning of this paper is showing us one more truth about our society: this is still a game led by men trying to catch other men, another Him. Have you seen any lady around recently?

Serbian translation published in Prelom Magazine No.6/7, June 2005

[1] Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, CNN news report at: http://edition.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/12/14/sprj.irq.saddam.profile/

[2] “The rule I have adhereted to, that I hold my students to, and that has been the most productive constraint I have experienced in my own practice, is to never just theorize but always to allow the object ‘to speak back’”.

[3] “Trough the visitor’s walking tour, going from one work to another, the narrative comes about. It is the walking tour that becomes the narrative. ” Ernst van Alphen, 2004: 166

[4] These works could be seen as elements that will frame the rest of the works seen later: self-portrait, then Minnie Mouse carying cat in the cage as a clear refference to Art Spiegelman’s cartoon novel, Maus, where the Nazis are represented as cats and Jews as mice: the choice to use Minnie Mouse as a main visual identity of the exhibition (posters for the exhibition, front cover of the catalogue, etc.) we can even interpret Idessa Hendeles as Minnie Mouse entraping the image of German history in order to discuss and negotiate the past for better future. Photograph Wild Bunch is representing the famous group of most wanted criminals in the USA at the beginning of XX century, a photograph that was made just for fun but which was the only trace for the police to identify and capture them, showing us the power that visual representations can have when used as evidence.

[5] “Welcome to the world of Maurizio Cattelan. Here, life is both comic and tragic, immediately recognizable and uttery strange. [...] He is a storyteller who’s always looking for – and finding – ways to slip in and around the comedy of human relations and tell us something about ourselves.” Bob Nickas, 1999

[6] “Not giving a precise direction to the work means you are giving it a longer life. So, the more issues it incorporates, the better. Maybe it’s no longer time to create crisis, but rather to reflect crisis in the piece itself. So, now I see that art has a great potential to refer to a broader debate, to go out there and reach an incredible audience. And if my work can’t do that, well, it’s useless.” Cattelan in Obrist, 2002

[7] We will come back later on some possible interpretations of this posture, reffering to a person that has really kneeled down, asking for forgiveness.

[8] French version was published by Les Presses du Reel, Dijon, France in 1998, and the English version by the same publishing house in 2002.

[9] Bourriaud – Relational Aesthetics – Glossary (Integral), at www.gairspace.org.uk/htm/bourr.htm

[10] Burio, 2002:4

[11] Burio, 2002:20

[12] Burio, 2002:28

[13] Burio, 2002:20

[14] Relations understood in a more wider way: you can see relations between herself and the environment she is making this exhibition for, than all the works exhibited are standing in certain relation between themselves, and in the Bourriaud’s sense, the last layer would be to see relations every particular work has with the global society it is reffering to.

[15] The person that reveiled this to me was my young German friend, and I think I should be proud of him.

[16] See results at: www.dhm.de/lemo/objekte/statistik/KontinuitaetUndWandel_umfrageKniefallBrandt/index.html

[17] The best example for this problem of German national identity and repression of memory has been shown in Wim Wenders’ film Der Himmel über Berlin (1987) with the story about the angels that don’t manage to be the part of the surrounding world. Without human existence and human experience they can not feel real life and create history, condemned to suffer forever.

[18] The most recent example is a documentary From Dachau With Love (Gruesse aus Dachau, 2003) made by young director Bernd Fischer who has grew up in this small Bavarian town but he doesn’t know anything about this part of the city history. His movie is an attempt to find out the truth. For details see: www.german-cinema.de/archive/film_view.php?film_id=772

[19] In the case of defining Europe here, we will use the most dominant definition of today: European Union seen as a ‘true’ Europe.

[20] “Veo ograničava raspoloživost Drugog za potrošnju. Veo opstruira ulogu koju egzotizovani Drugi ima u konstruisanju dominantnog 'Ja' i zaprečuje put – u ovom slučaju sa dodatnom seksualnom konotacijom – zadovoljstvu”, Terkessidis 2001:47

[21] Terkessidis, 2001:51

[22] Karakasoglu-Aydin 1998:466, as cited in Terkessidis, 2001:51

[23] Žižek, 1996:121

[24] First used and defined by Etienne Balibar, “Is there a ‘Neo-Racism’?”, in Etienne Balibar and Emmanuel Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class, Verso Books, London 1991, as cited in Žižek, 1997:120.

[25] Žižek, 1996:46

Bibliography:

Bal, Mieke

2002 “Concept” in Mieke Bal, Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: a Rough

Guide.

Bourriaud, Nicolas

2003, Relational Aesthetics – Glossary (Integral), www.gairspace.org.uk/htm/bourr.htm

Burio, Nikolas

2002, Relaciona estetika, Centar za savremenu umetnost –

Kerr, John

2003 “Foreward for EU Constitution Draft”, EU Constitutional Draft, www.prospect-magazine.co.uk/HtmlPages/Constitution.pdf

Lewis, Ben

2003 “Maurizio Cattelan: How to Get a Head in the Art World”, www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfour/documentaries/features/art-safari2.shtml

Nickas, Bob

1999 “Interview with

Cattelan”, www.indexmagazine.com/interviews/maurizio_cattelan.shtml

Obrist, Hans Ulrich

2000 “Interview”, www.undo.net

Prodi, Romano

2004 “Prodi

warning on two-speed

Terkessidis, Mark

2001 “Globalna kultura u Nemackoj, ili: Kako obespravljene zene i

kriminalci spasavaju hibriditet”, Magazine Prelom, Casopis skole za istoriju i teoriju umetnosti, Centar za savremenu

umetnost –

van Alphen, Ernst

2004 “Exhibition as Narrative Work of Art” in Ydessa Hendeles, Chris

Dercon, Thomas Weski, Partners: Ydessa Hendeles. Buchhandlung Walter König, Köln, 166-185

2000 “Where the Human Conditions and The Animal Kingdom Merge”, www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m1285/6_30/62798235/p1/article.jhtml

Žižek, Slavoj