Manifesta - European Biennial of Contemporary Art

That Never Happened:

Deleted Subjects and

Aborted Objects

“The exhibition is a tool of thousand-and-one purposes,

and half of them have not yet been discovered.”

Kenneth Luckhurst, The Story of

Exhibitions (1957)

In one of the earliest attempts to see exhibitions in all their

complexity and as objects for theoretical reflection and analysis, in the study

entitled The Story of Exhibitions written

half a century ago, Kenneth Luckhurst constructed a historical framework in

order to examine different modes of using exhibitions as cultural forms since

their birth in the late XVII century. Luckhurst’s analysis offers a wide scope

of potential functions that exhibitions were created to perform, from aesthetic

to economic, social, cultural, political, ideological, and educational ones.

The most important point of his analysis is summarized in the quote at the

beginning of this page, underlining the fact that purposes and functions of

exhibitions are constantly being transformed and negotiated according to

specific circumstances, hence a need for a critical eye to keep a close look

into this cultural form in order to examine ongoing processes of shifts and

modifications. These shifts are culturally and historically embedded hence it becomes

possible to get a specific insight into the context that produces exhibitions

in the first place. Exhibitions of (contemporary) art are specific sites that

are permanently ‘under-construction’, where new narratives and meanings are

produced with every next show, every next exposure.

The Western art world is still embedded in the modernist construction of

a ‘white cube’ as a guarantee of its separation and independence from the

outside world(s). This white and sterile form of exposure came to be considered

also a guarantee for an objective gaze in a neutral space out of time, and, as

Brian O’ Doherty argues in his influential essay from 1976, a space that

functions as a “stabilizing social construct” and a guarantee of social

stability (O’ Doherty, Inside the White

Cube, 1999:74).[1] Nevertheless,

this notion of independence and neutrality becomes complicated with the

entrance of the main agents of the relationship constructed within the

exhibition space: of art objects, on one side, and the viewers on the other.

Through them enters the outside world: art objects are not part of some

Immaculate Conception but products of specific circumstances and loaded with

different meanings through the act of exhibiting; from their side, the viewers

bring into this space the complex networks of relations and visual regimes of

perceiving the exposed objects. Therefore, the aim of the following analysis is

to show the ways in which ‘neutral’ space of exhibitions comes to be influenced

by the surrounding social, economic and political system, an influence that is

performed by various and dispersed agents and means.

I will focus my analysis on Manifesta - European Biennial of

Contemporary Art in order to define current transformations of contemporary art

exhibitions. This art manifestation was developed as itinerary and nomadic

biennial at the beginning of the 1990s, as an initiative of the Dutch

government and, although based in Amsterdam, it travels

to different host cities with each new edition. Manifesta was created as

A response to the political and economic changes brought about by the

end of the Cold War and the consequent moves towards European integration, it

aspired to provide a moveable platform that could support a growing network of

visual arts professionals throughout the region. (Manifesta Official Website,

visited October 23, 2006)

There have been six edition of Manifesta up to this date from which the

sixth one never happened due to severe escalation of confrontation between the

curators and officials of the city of Nicosia where it was planned to take

place and I will return to this example later in my analysis.[2]

What is important here is that this manifestation entails two important

concepts in its name: ‘European’ and ‘contemporary art’, where the first refers

to the political aspects of its activities and latter to the aesthetic ones.

Therefore, at the example of this biennial, it becomes possible to examine

current definitions of both of these concepts as proposed by Manifesta, as well

as shifts in political and aesthetic paradigms and their mutual interconnectedness.

The main point of departure of this analysis will not be the analysis of

what is being intentionally exhibited, but the quest to detect what usually stays

hidden behind this act, or rather, what agents involved in the production of

Manifesta discourses believe stays hidden or invisible. I will follow the

notion by which the exposed objects have a double function of pointing out the

discrepancy between the story they are supposed to tell and the story that they

actually tell when seen within a wider framework, as proposed by Mieke Bal in

her study on exhibitions entitled Double

Exposure (1996). In the case of the last edition of Manifesta, a biennial

that never happened, I will focus on what would have been exposed in the

exhibition whose curatorial concept have aborted artworks even before they were

conceived. Using the perspective of narratology as a way to read exhibitions,

undertaken to locate the constituted and potential speakers within this

constellation, the following analysis will pose the question: what can

silenced, aborted, or censored subjects and objects tell us about this

constellation of power relations to which they simultaneously remain implicit?

Secrets of the Manifesta Archive

My starting question in this analysis was how can I read Manifesta, European Biennial of Contemporary Art, as a cultural object, as an object of cultural analysis? In her introduction to The Practice of Cultural Analysis, Mieke Bal defines cultural analysis as interdisciplinary, self-reflective practice that “seeks to understand the past as part of the present” (1999:1), a practice that does not hide its origin but includes the cultural analyst in the analysis, as implicated part of the process. Taking in mind that, in this case, I have not seen any of the actual exhibitions of Manifesta biennials, my position as a cultural analyst became to analyze the traces where and meta-levels on which this manifestation is still happening in the present tense. However, since Manifesta’s official rhetoric underlines the importance of its archive which supposedly contains all information needed for any future scholar interested in this institution, I decided to start my research there.

Creators of Manifesta consider it to be a democratic institution and its publicly accessible archive as a guarantee of democratic principles. This archive is announced to be an open resource, “a mobile, growing and partially interactive documentation project accessible on the Internet and available for public consultation” at its Manifesta at Home office in Amsterdam. Since my main interest was in the curatorial practices of Manifesta biennials, during my visit there I asked permission to have insight into the documents on the selection procedure of curators and host cities. However, I was denied any access to these documents, for the reason, so I was explained, of “protecting the rights of curators”. To the email correspondence between the board members about the selecting of the last host city, Nicosia in Cyprus, I was given limited access. Instead of curatorial proposals, I was offered the proposals of rejected artists since their interests, as it seems, are not the ones to be protected. While being denied access to most of the things I was interested in researching, I was introduced, by the director herself, to a recent Manifesta’s publication, a luxurious and impressive 300-pages-long monograph on the history and mission of this manifestation, published by Manifesta itself and entitled The Manifesta Decade. This publication offers a wide historical overview and analysis of the influences this manifestation had in the past, including as its final chapter an overview of the archive as well. According to one of the editors, the archive is able to give “an act of re-experience” even to those who have never seen the exhibitions (Barbara Vanderlinden, 2005:232). Having in mind the obstacles in researching the ‘real’ archive, I decided at that point to focus on this particular segment, testing the Lacanian notion that if there were some symptoms, they must be visible in every event produced by the subject in question.

In practical terms,

cultural analysis is based on close reading, as an

active exchange of positions with the observed object that is allowed to

‘speak

back’ and lead the analyst to a direction she would never take on her

own. This

also means paying attention to details that can question previously

established

status and identity of the object in question and test a particular

theoretical

discourse through which it is being examined. In his approach to explore

the

archive, Jacques Derrida advices us to look for an event, a momentum

that will

open up the archive for critical reading through specific archeological

practice, when “the origin then speaks by

itself” (Derrida,

The Archival Fever, 1995: 58). Beside

this initial similarity between Derrida’s attempts, following Freud, to

search

for archeological moments, the practice of cultural analysis, as

proposed by

Bal, brings in an important additional element. In the first case, the

object,

the “archeological stone speaks by itself” (Derrida: 58) without

being aware of the theoretical framework that brings it

into discourse, while following Bal, the object that speaks back becomes

‘aware’ of the theoretical discourse: it is put in dialogue with it and

can

even contradict or break it up. In this case, the objects are never

pure, never

clean and innocent as Derrida (and Freud) wanted them to be. From the

moment of

their reappearance on the historical surface, the objects are already

embedded

into the specific theoretical discourse and one of the duties of the

cultural

analyst is to make this visible.

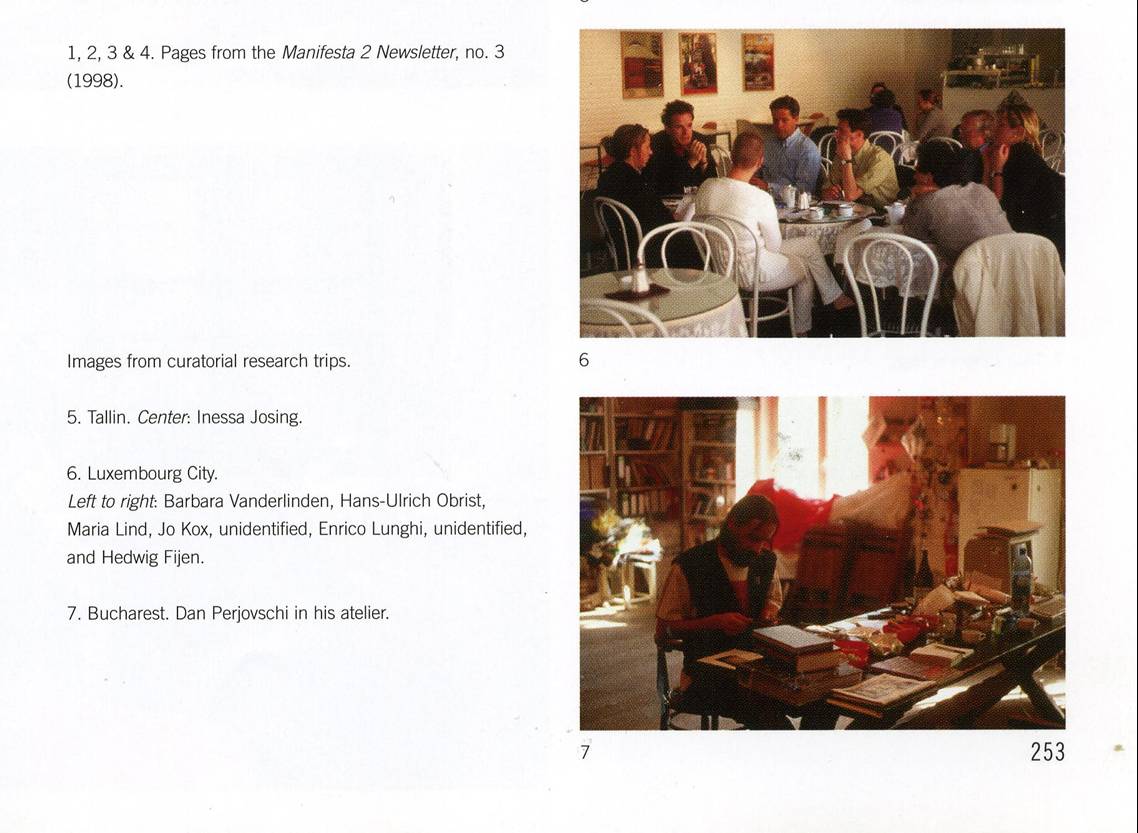

In the space of the Manifesta archive in the publication, among ‘miniature’ representations of the artworks from previous biennials, I had an unexpected encounter with something, or rather someone I did not expect to meet. This someone grabbed my attention at first glance and, since we have not been introduced before, soon became my main theoretical obsession. On numerous photographs of Manifesta curators and board members at official press conferences and ‘informal’ meetings in cafes, there was someone whom the caption referred to as ‘unidentified’. This unidentified person took on different shapes - on some pictures it was a woman, on others it was a man, and on some it duplicated itself. It moves freely from city to city, from country to country, following this itinerary art manifestation as a shadow. What shocks the most is the fact that these Unidentified persons are engaged in very close conversations with the main protagonists of the Manifesta decade, being part of panel discussions or just giving a friendly hug to the identified ones as a way to show their belonging to the depicted group. When encountered in the space of the archive, whose main function is to preserve memory, what the Unidentified immediately brings is not only the shortness of memory of those who were identifying these fairly recent pictures, but the failure of the archive to perform its function for which it was created at the first place.[3] As a consequence, I decided to follow the Unidentified one who has taken me to the direction I initially did not plan to go, to the analysis of the concept of the archive itself. Therefore, what I propose here is to read this unusual deletion, this unusual hole in the memory of the Manifesta archive side-by-side with the context that has produced it, the Manifesta’s official rhetorics and put its presumably democratic principles in a dialogue with Derrida’s accounts on the archive. My main question here is what this Unidentified one can ‘speak back’ about: at the very beginning, it clearly deconstructs the intention of this manifestation to have a full control over its historical image. As we can see, things (can) always slip out of control.

Deleted Subjects

In his attempt to bring out the archive of the Greek word Arkhe as the origin of the present uses of this term, Derrida reminds us of its double meaning, or two principles entailed in it: the principle of commencement and the principle of commandment. According to this, the archive is located in the house of the ones who command, who are not only the documents’ guardians but they are also the ones who are given “hermeneutic right and competence” that gives them the power of consignation: of unification, identification, classification and interpretation of the archive (Derrida: 10). This position means the power not only over physical objects, but over the historical discourse or the discourse of the commencement, of the origin based on the material traces guarded in the archive.

Although conceived and considered to be a nomadic, itinerary art manifestation, Manifesta has its home in Amsterdam and so does its archive. Created in the same decade when the informatic revolution took place and when the digitalization of archives was in its high, it seems unusual to encounter this retrograde tendency sustained by the argument that it would be impossible to move the enormous content of Manifesta’s archive from one host city to another.[4] Following Derrida, the physical location of the archive can be seen as the location from which power is being distributed, giving or denying the symbolic mandate to the ones who want to enter and interpret it. The need to control this process might come from the fact that, although Manifesta constructs this recent decade as remote history, it is run by the agents still very active and influential within the art scene, therefore the need to protect any document that could deconstruct their desired projected image. According to Derrida,

There is no political power without control of the archive, if not memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation. A contrario, the breaches of democracy can be measured by (…) Forbidden Archives” (Derrida: 10-11 in the footnote).

As previously noticed, my first steps into the ‘real’ archive of Manifesta were limited with the detection of invisible borders not to be crossed and, as a consequence, the democratic principle of this institution becomes severely compromised with the discovery of the Forbidden Archive. Instead, through this attempt to control the archive, Manifesta shows a desire to control the image of its recent past as well and immediately profit from this self-created historical mandate. This practice is not unusual or expressed by this institution only, but when presented in the guise of democratic principles, it becomes problematic.[5]

The ideal archive every archivist attempts to create is one that exists and functions as a single corpus, as a coherent body that nothing can divide or destroy. Archivist’s power of consignation treats the historical documents as part of a larger, coherent story, of a singular picture without cracks. Or, in Derrida’s words, “in an archive, there should not be any absolute dissociation, any heterogeneity or secret which could separate (secernere), or partition, in an absolute manner.” (10) This desire of the archivist to have the absolute power over the corpus of the documents it ‘guards’ and to present history as a narrative without tensions or contradictions, becomes destabilized by the appearance of the Unidentified one. Hidden within the surrounding homogenous discourse, the Unidentified one manages to pass through its cracks and speak out. As we have learned, “the archive always works, and a priori, against itself” (Derrida: 14) and the Unidentified one embodies exactly this sickness, this desire of the archive to destroy itself.

The reason for this desire of the archive to destroy itself is in its hypomnesic character, since it has been constructed as exterior technical model of the psychic apparatus. Defined this way, Derrida argues that archive cannot escape the drive that originally haunts human psychic apparatus – the death/aggression/destruction drive. Therefore, the archive is built on the unstable ground constantly endangered by its inherent contradictions of the desire to remember and the drive to erase from the memory. Nevertheless, “this contradiction is not negative, it modulates and conditions the very formation of the concept of the archive” (Derrida: 90). If we go back to the Unidentified one, she is born exactly in this void, at the place where she still exist as a trace of a deletion, as a phantom between two worlds. What follows is that this secret of Manifesta archive and its failure to preserve past events from the deletion becomes exposed, as well as the accuracy of its historical narrative constructed on this ground. Thanks to the Unidentified one, to this phantom of the archive, we are allowed to enter it and gain this insight without the control of its guardians.[6]

According to Derrida, we live in times when everybody burns with the desire to archive, where each of us is possessed by le mal d’archive or archival fever (14). What this sickness means is “to have a compulsive, repetitive and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.” (57) What can the Unidentified one, as a resident of the place where the archive anarchives itself, tell us about the nostalgic spot to which the archive of Manifesta wants to go back? The answer seems clear and simple, if we search for the moment Manifesta takes as the moment of its birth: it is the year 1989, the year of its arkhē, of its beginning of counting time.[7] Nostalgia also occurs as the effect of the significant even traumatic events and, following this, the year 1989 can be read as a traumatic moment in the Western art discourse, as a moment of major political and social changes in recent European past. If seen this way, Manifesta becomes a strange monument for the times before the occurrence of this trauma, revealing the nostalgic mourning for the times already gone. Following the Unidentified one through the archive and its symptoms, we have arrived to the political level of activities of Manifesta or the primary reasons it was created for - to assist the encounter with the Others in the new chapter of European history.

This chapter of European history is characterized by the attempt to create a stabile and unique cultural and political identity of the European Union summarized in one of its official slogans ‘United in Difference’. Nevertheless, this discourse of ‘unity of differences’ points out its homogenizing tendencies that are inherently undemocratic, hence the real democratic position would be ‘difference in unity’ or the flexibility to accommodate all the heterogeneous traits this unity contains. What connects this process with the previous discussion on the archive, according to Derrida, is the fact that both processes are impossible without violence:

The gathering into itself of the One is never without violence, nor is the self-affirmation of the Unique, the law of the archontic, the law of consignation which orders to archive. Consignation is never without that excessive pressure (impression, repression, suppression) of which repression and suppression are at least figures (Derrida, 50-51).

As discovery of the Unidentified one in the Manifesta archive testifies, the Other is not anymore at the other side of the border, somewhere in the far East. The Other has crossed the line and infiltrated within Us. The Unidentified one seems to be created at this spot where the Other is allowed to enter the official discourse but denied identity, denied a proper name, that way staying the unidentifiable Other forever. Radical deletion of the nameless Other is happening in her full presence, testifying about her existence in limbo, between two worlds, where the democratic principle of equality is being practiced only on the level of rhetoric. If we take into account the view on current political process as proposed by Giorgo Agamben, it is possible to see the Unidentified one as the embodiment of someone he names ‘homo sacer’, of someone who is legally dead, deprived of a determinate legal status, while biologically still alive. Thus, Agamben argues, "the so-called sacred and inaliable rights of man prove to be completely unprotected at the very moment it is no longer possible to characterize them as rights of the citizens of a state" (1998:199).[8] In the case of Manifesta, it seems that we deal with a translation of this same practice into the realm of culture where the institution created to accommodate ongoing shifts could not prevent the internalization of the processes it was trying to fight against. One seems to be not aware of its own split, of its own divisions and cracks of the picture of the ideal Self, the split necessary for it to exist in the first place .

The main mechanism of the violence, whether encountered as the archival impulse or unifying process of the Self, is repetition. According to Derrida, “the One, as self-repetition, can only repeat and recall this instituting violence. It can only affirm itself and engage itself in this repetition. This is even what ties in depth the injuction of memory with the anticipation of the future to come.” (Derrida: 51) In the case of Manifesta exhibitions, the traces in the archive testify about the process of repetition:

The absence of radically different selection procedure in all five editions of Manifesta suggests that, even if the curators were not pressured to conform to a pre-established model, they voluntarily acted as if they were under such pressure. (…) [Moisdon Trembley] also evoked the ineffectiveness of repeating the intensive trans-European survey that the curators of the previous Manifesta edition had performed only a year and a half before: “An art scene, or context, does not renew itself that quickly.” (van Winkel: 226)

In order to exist, Manifesta has to repeat itself, repeating the same violence against itself and against the Other, with every new edition, every new exhibition. The archive is the record of this violence but also a way to assure future developments, since the archive does not only record events, it also produces them, or, according to Derrida, it produces the criteria by which the future events will be archivable. (17) Hence, the control of the archive means not only control over the past, but control over the future as well.

Caught within this

circle of repetition, the question to be posed here

is what are the options left for the subjects to escape it as well as

its

inherent violence? In his analysis of the archive, Derrida gives a short

but theoretically

valuable connection between the creation of archive and creation of art

works

through the activity of the death drive: “the death drive tends thus to

destroy

the hypomnesic archive, except if it can be disguised, made up, painted,

printed, represented as the idol of its truth in painting.” (14)

Possible

interpretation of this insight is that the repetition and the

destruction of

memory can be escaped if the death drive is turned into the “lovely

impressions” that become “memories of death” (Derrida: 14). According to

this,

the disappearance or deletion of the art objects takes away the

possibility of

creating a difference, difference that can break the circle of

repetition of

violence. In the next part, I will take a look what are the possible

theoretical

implications of the deletion of art objects as proposed in the

curatorial

concept of Manifesta 6.

Aborted Objects

What would we find in the archive in the hypothetical situation in which the planned Manifesta 6 did happen the way it was planned? Similar to the previous discovery of the Unidentified ones, the trace we would have to follow is not the one behind the things or events that did happen, but the ones left as a void behind the ones that did not happen. In this case, there would be no trace left of the artworks: through this act of erasure, the art objects would incidentally and definitely disappear from the archive. Nevertheless, this occurrence should not be considered to be uniquely part of Manifesta practice alone.[9] Rather, this tendency in curatorial practice to shift its main focus from the art works has occurred at the same time when curating went through the process of redefining its practice in the Nineties. This new type of curators is usually referred to as ‘independent curators’, where independence relates to the flexible, “nomadic, traveling elite” officially not employed by one particular institution (Vanderlinden, 1998: 210). The process of ‘nomadization’ of curating has put one more demand on this profession: curators must be not only experts of art but, more importantly, experts of local cultures. As Francesco Bonami defines it, “the role of the curator today involves such enormous geographical diversity that the curator is now a kind of visual anthropologist – no longer just a taste maker, but a cultural analyst.” (Bonami in Boutoux, 2005:204)

Since these times, the discussions in curatorship have shifted from broad aesthetic ones to social and political issues. Or, as Camiel van Winkel concludes

This generation of curators barely alludes to the fact that curating entails showing works of art to an audience; they seem to be more interested in other aspects of their job. (…) This also explains why the desire to generate aesthetic experience is completely absent from the Manifesta discourse. The curators see the aesthetic experience as a static and private moment that makes the process of a dialogue and creative exchange – and thus the social dimensions of the work of art – turn inward and evaporate (2005: 228).

In the example of the ‘Manifesta Archive’ in the publication I was using to read through this manifestation, this tendency is evident in the apology of the editors for not having enough space for the visual images of all works to be fully reproduced. The reason for the lack of pictures of artists was explained as an attempt to avoid the “romantic notion of the mastery of the artist, showing shots of him or her at work, to make the artistic craftsmanship visible and create an illusion of intimate participation. A contemporary version of the “grand masters” is not of interest here.” (Vanderlinden, 2005: 236). Nevertheless, there was enough space to include numerous photographs of curators at work, of them visiting artists, visiting remote countries, having hard thoughts, or having public discussions. What happened here is the substitution of this “romantic notion” of the artist with the image of the curator. Characterized by Vanderlinden as “one of the leading artistic forms of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries” (236), the exhibitions have officially been recognized as a form and the curator is the one who molds them.[10] The artworks are there because they cannot be evaded or, as seen in the case of Manifesta 6, perhaps they even can.

What matters here is the question what else is being erased through this act of erasing the artworks before they were conceived. As art history teaches us, twentieth century brought new shifts in the experience of the visual representations and what is to be considered as Art, from Surrealists and Breton’s found objects and Duchamp’s readymades, to the Sixties and the first cycle of dematerialization of art as an attempt to escape commodification within the dominant system of capitalistic production. Nevertheless, what makes this current shift different is that the motivation to temporarily put artworks aside came not from the artists, as in previous times, but from the curators. In this case, when the disappearance of the object became a curatorial concept rather then a part of artistic strategy, the third part of the exhibition triad - art work, curator, and viewer - has disappeared as well. At the moment when art works were aborted and expelled from the site, there was no place left for the outside world to enter. In the case of the dematerialization of objects as artistic strategy, the whole process depended on the viewer, who had to be present for the dematerialization to happen. The only exhibition we would be left with in the case of Manifesta 6 is the exhibition of the established relations between attending curators and artists, adding a new function exhibition is created to serve, one that was probably hard to imagine in the Luckhurst times.

If the objects are aborted, what is, then, Manifesta’s attitude toward cultural contexts that host its itinerary editions? The particular ‘insensibility’ of Manifesta curators for local contexts, local institutions and people has been noticed years ago.[11] Constructed as a manifestation whose economic existence depends largely on the budget of a local host, Manifesta was soon turned into an economic enterprise and a brand to be desired and competed for by most of the European cities who desire to promote their ‘positive’ image in the wider political and cultural agenda. From this perspective, Manifesta resembles more a virus than a nomadic construction it desires to be seen as, where ‘Manifesta at Home’ is it place of residence. What makes this practice different from the old colonial attitude is its complicity: within this construction, the host participates voluntarily, paying a high price for the benefits it gains from the virus it hosts. Brought to work within limits of this constellation, the curators turn to be nothing more then cultural tourists, who at the end of the process bring home their own picture projected to different local contexts.

The most recent escalation of the ‘misunderstandings’ curators had with the local context happened in 2006 when Nicosia, Cyprus was selected to host this edition of Manifesta. This particular location has been selected by the Manifesta Board over Tallinn, Estonia for its specific political and cultural present, as the closest spot in which, according to them, Europe touches the Orient, or the Middle East:

And of course it’s about the location that is between real West and real East. Not to mention beautiful southern climate and historical sites. (…) The choice is very difficult having in mind that Manifesta 6 in both Tallinn and Nicosia will be a metaphorical confirmation of European expansion of EU of culture. (Jara Boubnova, email correspondence, May 12, 2004, Folder “Nicosia” in Manifesta Archive)

As it seems, the selection of Nicosia follows current political shifts in Europe where its former East has moved further south, and the opportunity to have a first edition in the country of the former Eastern Block was hence missed. What might worry the most from the issues that dominated the official discourse of debate around cancellation of Manifesta 6 was the insistence that the cause for the ‘misunderstanding’ should be found in the local context. The conflict between the Greek and the Turkish side was constantly in focus, but what stayed hidden all the time was the fact that Cyprus is actually divided into three parts: the Greek, the Turkish and the British.[12] From this perspective, the independence Cyprus gained in 1960 should be perceived as a moment when all the trouble started; in the same time, its colonial past seems as an orderly utopian dream. The decision of curators to set a school and leave out of their focus the specific historical and political circumstances of this island turned their enterprise into an extended holiday that could have taken place on any other ‘exotic’ spot on Earth. As it turns out, the decision to abort art objects has erased also any possibility for critical reflection on the circumstances Cyprus finds itself today.

If we try to read this disappearance of object as a symptom, it will bring us to the expertise of psychoanalysis where objects or, rather, the lack of objects is considered to be a key element in the formation of subjectivity as well as in the economy of drives and desires. As Slavoj Žižek argues, the relation to the desired objects forms a basis of the relationship the One has with the Other:

What bothers us in the Other (Jew, Japanese, African, Turk) is that he appears to entertain a privileged relationship to the object – the other either possesses the object treasure, having snatched it away from us (which is why we don’t have it), or he poses a threat to our possession of the object. (1998: 999)

Going back to the previous analysis of Manifesta archive and the discussion about what loss we could speculate it was created to hide and what traumatic event it refers to, European unification brought as well a temporary deconstruction of the European Other. In the clinical experience of psychoanalysis, the patients who have lost their admired object cannot proceed to the phase of mourning since they need a “symbiotic, idealizing type of identification with their objects in order to stabilize their identity.” (Weiss and Lang, 2000:326) In the case of European political shifts and the ‘traumatic’ moments in the process of creating a unified One, this symptoms could be interpreted as a continuous need to replace the lost object, the idealized Other, with the new idealized Other in order to stabilize fragile identity. In Lacanian terms, the evolution of subjectivity is linked to a fundamental symbolic process, in which “the relationship to the Other is transformed into a symbolic one. (…) In the moment that the primary Other can be symbolized (...) the possibility to distance oneself arises and thereby the beginnings of a space where an own identity can be developed” (326).

This ability to symbolize the relationship with the Other brings us back to the position of art works as objects that can serve as a way to temporarily stabilize one’s continuously unstable identity. What can also be read from the act of erasure of art objects in curatorial practice is a disbelief in the possibility of the artists to present new insights through their works, or new ways to symbolize their relationship with this Other – a historically, politically and culturally rich island. Cyprus seems to be used as a setting, a scenography for the proposed art school, a move that has blocked alternative interpretations of reality and destabilization of dominant discourses.

Manifesta Democracy Revised

As the discovery of the Unidentified ones in Manifesta archive proved earlier, the democratic nature of this institution has been severely compromised. At this point, I was interested into what this same phantom can say about two other aspects on which Manifesta bases its democratic character: functioning as a network and practicing active self-criticism. As we read

Manifesta developed into a fast growing network for young professionals in Europe and one of the most innovative biennial exhibition programme to be held anywhere. This is due, in no small measure, to its pan-European ambitions and its uniquely nomadic nature. Both the network and the exhibition, with its related activities are equally important components of this itinerant event. (Official Manifesta Website, visited January 5, 2007)

Interpreted this way,

networks are assumed to have an inherent

democratic nature. Nevertheless, as Camiel van Winkel has noticed in his

critical analysis of Manifesta rhetorics,

Networks are not inherently democratic. On the contrary, a network is exclusive rather than inclusive, built upon a set of privileged relations between selected individuals. What place does the public occupy in relation to the network? (…) Ascribed as simply open to the public, to “everyone” (…) the discourse is of such a general and abstract nature that any notion of privilege or exclusion evaporates. (2005: 221)

Hence, the network per se has a democratic potential, a potential to be an instrument of democratic procedure, but as long as it is practiced as an entity to include there will always be the ones who are excluded. The projected picture of the Manifesta network of happy individuals, of Manifesta ‘family’, becomes broken in the moment we perceive the Unidentified one in the picture. The Unidentified one speaks about this position of being excluded, of being nameless, irrelevant and unrecognized although having the same physical, bodily traits as the identified ones. Trough this, one more power of the archivist becomes visible: the authority to name things, in this case people, and position them in the discourse, giving them the name and identity, giving them the history or denying them the right to speak. The un-networked ones are dismissed by the archivist as the unidentifiable ones, left alone at the other side. The network fails to perform its democratic potential; instead, it serves a particular function to hide the actual authority figures who would be disposed if the democratic transparency was real.

In this same rhetoric of the free interpretation of basic concepts of democracy, “in the Manifesta language game, ‘democratic’ means ‘open’ and ‘inclusive’ but also ‘open-ended’” (van Winkel, 2005: 221) and it has been practiced by its curators as well. All these strategies (open-ended, process-based approaches) are evidently practiced trough the critical attitude Manifesta takes towards its own practice. They are the strategies Manifesta employs to survive attempts of external criticism. Through this rhetorical move, the failure is turned into success:

The final result is valued less than the path followed in order to achieve it. With it, the possibility of a failure can be openly acknowledged and even thematized. (…) Thus the built-in option for curators to admit and elaborate their own “failure” paradoxically contributes to the rhetorical construction of Manifesta success. (van Winkel: 222)

This strategy becomes visible in the case of the Unidentified one as well. Through the act of giving her (any) name, the archivist hides her failure to perform her function, hides the mistakes and slips of memory that are incorporated into her version of this particular history. The failure is incorporated into the discourse where this impossibility or unwillingness to research and reveal the identity of the persons encountered just a few years ago does not turn the caption into some general description like “the curators and panelists”, but reveals openly its own failure to give a name to the people who contributed to this history in the first place. Hence the picture and the caption seem all in order once we look at them: the image is there, the names are there, and the ones we do not remember also have names. Through this practice, Manifesta does not deconstruct nor destroy the authoritarian nature of curatorial (and archival) practice; instead, it hides them behind the basic postulates of democracy. The travesty of democracy is revealed thanks to the deprived Unidentified one.

The remaining question here is should we put all the blame for the rhetorical and free interpretation of democratic postulates on this art manifestation that might be only the one who manifests the symptoms of the same practice done in the wider political discourse. Sometimes being accused to be “an extension of Brussels’s cultural policy” and “complicit in the current official disappearance of immigrants in Europe from its cultural institutions” (Okwui Enwezor, 2005: 184), Manifesta leads us further to the question of the possibility to read ‘Europe’ through its art biennial. Hence, how does this ‘Europe’ look like in the scope of current political developments?

In her study of recent European movies that deal with current issues of the relationship with the Other and cultural and political processes, Yosefa Loshitzky chooses one particular scene from the film JOURNEY OF HOPE (1990) as the “ultimate iconic image of Fortress Europe”. In this scene, hungry and freezing refugees, who have just survived the harsh winter mountain storm, desperately knock on the double-glazed glass windows of a warm, indoor swimming pool inside an Alpine spa hotel. They see the owner of the hotel swimming in the pool, but because of soundproof glass walls, he cannot hear the refugees’ desperate cries for help:

Perhaps this shocking image of reflective duality of privilege mirrored by its counter-image of a luxury spa hotel turning into a hospital of potential deportees is the ultimate iconic image of Fortress Europe guarding its visible wealth and comfort against the pledge of non- Europeans in search of a better life. The image of ‘hospitality’ denied is the image of the New Europe (Loshitzky, 2006: 754).

The

important detail in this image, in this frame, is the disappearance of the voice. The visually present Others are denied the power to communicate by the institution of the sound-proof double glass. In this scene, the subalterns do speak,

even

shout, but nobody is able to hear them. The visual presence of the Other is not able to disturb Us anymore: their voice is stacked somewhere in the middle, in the

invisible space between two layers of glass. A similar analogy of ‘tolerance’ seems to be noticeable in the treatment of art works as reflected in the current curatorialpractice: the artworks

are put on a pedestal but protected with this

double glass that

will

not allow their

voice

to

be heard. Censorship no longer means

radical

destruction of artworks; rather, art works are turned into background illustrations,

into wallpaper

images

not to be reflected on.

Nevertheless, this attitude of Europe toward its Others is nothing new in European history, as Saskia Sassen shows in her recent analysis:

Today we deal with different religions and phenotypes and cultures, and we think that is the reason for the difficulty of incorporation. Our very European history suggests we had feelings of similar intensity about those who from today’s perspective appear to be ‘one of us’: the Germans, the Belgians, the Italians, just about any of the current EU membership. Given the acts of violence and the hatreds we felt against them, I cannot help but wonder whether those who we experience today as so different and difficult to assimilate will not undergo the same transformation over the coming generations. (2006:645)

Although comforting, these historical facts should not be used as an excuse for present crimes, for all these erasures, deletions, mutilations we are witnessing today. The ones in power would like these unidentified, undocumented, nameless, and hidden ones to stay that way. In this journey on which the Unidentified one has taken us to, the role of cultural analysis was not to discover the historical or archival ‘blind-spots’ and find the ‘real’ names of the Unidentified ones but, rather, to read these erasures as signs, as symptoms that point to deeper and bigger problems then what was assumed at first glance. The role of cultural analysis is to make these invisible glass borders visible, to find cracks through which the voice of the Other will be able to pass, to discover the voice that will be able to speak back. As it seems, the same way Europe will need to include the Others as its legal citizens in order to exist, it will need new artworks as well as a way to create a difference and destabilize current homogenizing political and cultural discourses. Once again, the One should not be afraid of the cracks on its idealized picture.

(Written in 2006. Unpublished manuscript, part of my PhD research)

[1] For a detailed analysis of the survival of the paradigm of the ‘white cube’ see in: Elena Filipovic, “The Global White Cube” (2005).

[2] Although created to make a bridge between the Eastern and Western Europe, most of Manifesta editions took place in the former West: Rotterdam (1996), Luxembourg (1998), Ljubljana (2000), Frankfurt (2002), Donostia - San Sebastian (2004).

[3] Strangely enough, on some of the photographs we find the editor of the archive, Vanderlinden, as being engaged in a vivid talk with theUnidentified ones.

[4] Selective and very limited insight into this archive is offered through the digital archive of the organization Basis-Wien that was commissioned byManifesta to digitalize parts of its archive. For more see: www.basis-wien.at.

[5] The attempt to present the presentation of the archive in order to materialize the concept of full democracy happened in one of the Manifestaexhibitions as well. The curators of Manifesta 4 decided to create an exhibition item out of the files of all the thousand artists they visited during theirexploration trips across Europe. This “administrative monument” (van Winkel, 2005: 222), was supposed to create an atmosphere in which nobodyfeels excluded, but instead hide the inherent (non-democratic) element of the curatorial practice that is based on the process of selection, thereforeinclusion and exclusion. Not taken as a main curatorial concept that could have turned the exhibition into these collections of artists’documentations, the existence of this archive together with the selected, exhibited art works just seems like a politically correct version of exclusorypractice of curatorship.

[6] “I tried to show elsewhere that though the classical scholar did not believe in phantoms and would not in truth know how to speak to them,forbidding himself even, it is quite possible that Marcellus had anticipated the coming of a scholar of the future, of a scholar who, in the future and soas to conceive of the future, would dare to speak to the phantom.” Derrida: 29

[7] Consequently, the first chapter in Manifesta Decade is entitled “One Day Every Wall Will Fall: Select Chronology of Art and Politics after 1989”and dedicated to the selected facts and figures from art and politics after 1989. Through this symbolic act, the counting of Manifesta time officiallystarts from this year.

[8] The most flagrant example of this deletion is discovered in Slovenia, one of the Manifesta ‘hosts’: “On 26 February 1992, at least 18,305(3) individuals were removed from the Slovenian registry of permanent residents and their records were transferred to the registry of foreigners.Those affected were not informed of this measure and its consequences. The "erased" were mainly people from other former Yugoslav republics,ho had been living in Slovenia and had not applied for or had been refused Slovenian citizenship in 1991 and 1992, after Slovenia became independent. As a result of the "erasure", they became de facto foreigners or stateless persons illegally residing in Slovenia. In some cases the "erasure" was subsequently followed by the physical destruction of the identity and other documents of the individuals concerned. Some of the"erased" were served forcible removal orders and had to leave the country.” More on the case of Slovenian “erased” ones see in: Slovenia AmnestyInternational’s Briefing to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 35th Session, November 2005, http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/engeur680022005 , visited January 2, 2007. w

[9] Curatorial concept for the Manifesta 6 is defined as being part of the ‘didactic turn’ in curatorship, as named by the editors of the Dutch art magazine Metropolis M. This turn limits the function of exhibitions to their didactical value, excluding the possibility of viewers to gainknowledge through a wider sensory perception. For more see: Metropolis M, Expanding Academy, 2006.

[10] This same period brought up the tendency of curators to ‘mold’ not only art works, but the social relations and political processes as well. Thisprocess has been named as relational aesthetics by the French curator Nicolas Bouriaud. For more see in: Nicolas Bouriaud, Relational Aesthetics(2002).

[11] For a detailed analysis of the attitude Manifesta curators and the negative consequences on the local art scene in the case of Ljubljana see morein: Thomas Botoux, “A Tale of Two Cities” (2005).

[12] The official reason for the cancellation is the refusal of the Greek side to financially support part of the school that was to take place in the Turkish zone: “a conflict has arisen

between Manifesta and Nicosia for

Art

Limited

(NFA). Manifesta

maintains

that

NFA, a

special

legal entity

set up

by representatives of the Municipality of Nicosia and the Cypriot Ministry of Culture and Education to administer Manifesta 6 in autumn 2006, has not fulfilled its contractual obligations to secure the selected venues by the curators in the entire city, i.e. in both North and South Nicosia.” Official explanation of the International Foundation Manifesta,

http://www.artfacts.net/index.php/pageType/instInfo/inst/6058/contentType/news//nID/2943/lang/1, visited October 23, 2006.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio

1998 Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford University Press

Amnesty International Official Website

“Slovenia: the ‘erased’ – Briefing to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights”. http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/engeur680022005

Artfact Official Website. http://www.artfacts.net

Bal, Mieke

1996 Double Exposures: The Subject of Cultural Analysis. London & New York: Routledge

1999 “Introduction”. Bal, Mieke (ed.)The Practice of Cultural Analysis: Exposing

Interdisciplinary Interpretation. Stanford: Stanford University Press: 1-14

Basis-Wien Official Website, Dokumentationszentrum, Archiv und umfangreichste

Datenbank zu zeitgenössischer Kunst, http://www.basis-wien.at

Bouriaud, Nicolas

2002 : Relational Aesthetics. Dijon : Les Presses du Réel

Boutoux, Thomas

2005 “A Tale of Two Cities: Manifesta in Rotterdam and Ljubljana”. The Manifesta

Decade: Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall

Europe. Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 201-218

Derrida, Jacques

1995 “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression”. Diacritics 25 (2): 9-63

Enwezor, Okwui,

2005 “Tebbitt’s Ghost”. Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe. Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 175-188

Filipović, Elena,

2005 “The Global White Cube”. The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary

Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe, Massachusetts: The MIT Press:

63-84

Filipović, Elena, Rafal B Niemojewski, Barbara Vanderlinden

2005 “One Day Every Wall Will Fall: Select Chronology of Art and Politics after

1989”. The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and

Biennials in Post-Wall Europe, Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 20-44

Folder “Nicosia”

2006 Manifesta at Home Archive

Loshitzky, Jozefa

2006 “Journeys of Hope to Fortress Europe”. Third Text 20 (6): 745–754

Luckhurst, Kenneth W.

1951 The Story of Exhibitions., London &New York: The Studio Publications

Manifesta Official Website, http://www.manifesta.org

Metropolis M,

2006 Expanding Academy. Utrecht: Metropolis M Foundation

O’ Doherty, Brian

1999: Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkley, Los

Angeles, London: University of California Press

Saskia Sassen

2006 “Europe’s Migrations: The Numbers and the Passions are Not New”. Third

Text, 20(6): 635-645

van Winkel, Camiel

2005 “The Rhetorics of Manifesta”. The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe.Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 219-232

Vanderlinden, Barbara

1998 “Futurables”. Manifesta 2, European Biennial of Contemporary Art, Luxembourg City: Casino Luxembourg-Forum d’artcontemporain: 207-211

2005 “The Archive Everywhere”. The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary

Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-Wall Europe. Massachusetts: The MIT Press:

233-238

Vanderlinden, Barbara, Elena Filipović

2005 The Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contemporary Art Exhibitions and

Biennials in Post-Wall Europe. Massachusetts: The MIT Press

Žižek, Slavoj

1998 “A Leftist Plea for ‘Eurocentrism’”. Critical Inquiry 24 (4): 988-1009

Filmography:

Xavier Koller

1990 Journey of Hope (Reise der Hoffnung)